John Sykes

John Sykes | |

|---|---|

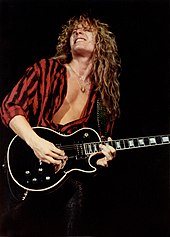

Sykes in 2008 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | John James Sykes |

| Born | 29 July 1959 Reading, Berkshire, England |

| Genres | |

| Occupation(s) |

|

| Instrument(s) |

|

| Years active | 1980–present |

| Formerly of | |

| Website | johnsykes |

John James Sykes (born 29 July 1959) is an English guitarist, best known as a member of Whitesnake, Thin Lizzy and Tygers of Pan Tang. He has also fronted the hard rock group Blue Murder and released several solo albums.

Following a stint in the heavy metal band Tygers of Pan Tang in the early 1980s, Sykes joined Irish hard rock group Thin Lizzy for their 1983 album Thunder and Lightning. He then joined Whitesnake, with whom he recorded the multi-platinum-selling self-titled seventh 1987 album. However, Sykes was let go from the band before the record's release under acrimonious circumstances, which led to him forming his own group Blue Murder. After two albums and a live record, he embarked on a solo career. For the remainder of the 1990s and early 2000s, Sykes split his time between his solo career and a reformed Thin Lizzy, which he fronted until 2009, when he left to focus on his solo career.

Influenced by the likes of Jimmy Page, Ritchie Blackmore and Gary Moore, Sykes is known for his distinctive playing style, characterized by his fast alternate picking, use of pinch harmonics, and sense of melody. In 2004, he was included on Guitar World's list of "100 Greatest Heavy Metal Guitarists of All Time". In 2006, Gibson released a limited line of John Sykes Signature Les Pauls, which were modelled after his 1978 Gibson Les Paul Custom.

Early life[edit]

John James Sykes was born 29 July 1959 in Reading, Berkshire.[1][2] He first became interested in the guitar at age fourteen, when his uncle showed him how to play some of Eric Clapton's licks.[3] At the time, Sykes and his family were living in Ibiza, Spain, where his father and uncle owned a discothèque. For the next two years, Sykes practiced playing blues songs on an old nylon-string guitar. After three years in Spain, the Sykes family moved back to Reading. There, John entered a relationship and essentially gave up the guitar for a year and half. He didn't start playing again until he moved to Blackpool, when he was asked to join the band Streetfighter by his friend Mervyn Goldsworthy, who would later play bass in Diamond Head, Samson and FM.[4]

Career[edit]

Early career[edit]

Sykes began his professional music career when he left Streetfighter to join Tygers of Pan Tang.[1][3] Sykes recorded two albums with the group, Spellbound and Crazy Nights, which were both released in 1981. By the following year, however, Sykes had grown frustrated with the band, as he and vocalist Jon Deverill would often butt heads with the other members.[5] He would later also state that in his opinion the group lacked both the style and dedication to achieve major success.[4] Sykes eventually left Tygers of Pan Tang two days before the start of a French tour in early 1982.[2] However, he did appear on two tracks on the band's fourth album The Cage, which was released after he had already left the group.[6]

After leaving Tygers of Pan Tang, Sykes auditioned for Ozzy Osbourne's band and was briefly a member of John Sloman's Badlands.[3][4] Despite a few shows and Sloman procuring a recording contract with EMI, the band ultimately broke-up after Sykes was approached to join Thin Lizzy.[7]

Thin Lizzy[edit]

After his departure from Tygers of Pan Tang, Sykes was still contractually obligated to deliver a single to the band's record label MCA Records. Through Tygers of Pan Tang producer Chris Tsangarides, Sykes was able to get in touch with Thin Lizzy frontman Phil Lynott. The two co-wrote and performed the single "Please Don't Leave Me", which was released in 1982. The track also featured fellow Thin Lizzy members Brian Downey and Darren Wharton.[8][9] After finishing the song, Sykes was asked to join Thin Lizzy. He was officially confirmed as the band's new guitarist in September 1982.[9] Sykes performed on the group's 1983 album Thunder and Lightning, for which he also co-wrote the single "Cold Sweat".[10][11] Sykes's inclusion helped revitalise the band, steering them towards a sound more akin to heavy metal.[12] The supporting tour for Thunder and Lightning was billed as Thin Lizzy's farewell tour, though Sykes and Lynott were eager to continue further.[13] During the tour, the band recorded the live album Life, and Sykes also accompanied Lynott on a European solo tour.[14] Thin Lizzy played their final UK concert at the Reading Festival in August 1983, before finally disbanding after a show at Nuremberg's Monsters of Rock festival on 4 September.[15]

Phil Lynott died on 4 January 1986, aged 36.[16] In 1994, Sykes, along with former Thin Lizzy members Brian Downey, Scott Gorham and Darren Wharton, formed a new touring version of Thin Lizzy, which was presented as a tribute to Phil Lynott's life and work. While the band only performed songs from Thin Lizzy's back catalogue and did not compose any new material, they were still criticised for using the Thin Lizzy name without Lynott being present.[17][18] In 2000, the group released the live album One Night Only.[8] Sykes continued to front Thin Lizzy through various line-up changes before announcing his own departure in 2009, stating: "I feel it's time to get back to playing my own music."[19] Scott Gorham would later reform Thin Lizzy without Sykes's involvement.

Whitesnake[edit]

After Thin Lizzy's break-up, Sykes was initially keen to continue working with Phil Lynott in what would become Grand Slam.[9] However, he was soon asked to join English hard rock group Whitesnake, whom he had met while on tour with Thin Lizzy.[8] After negotiating a satisfactory contract and receiving Phil Lynott's blessing, Sykes agreed to join Whitesnake.[6][10] He made his live debut with the group in Dublin on 17 February 1984.[20] He was then tasked with recording new guitar parts for the US release of the band's 1984 album Slide It In.[6] Afterwards, Whitesnake embarked on a lengthy world tour, which culminated in two shows at the 1985 Rock in Rio festival.[21] Slide It In became Whitesnake's first major success in the United States, selling over half a million copies. Sykes played a key role in Whitesnake's newfound success, with a more vibrant look and sound compared to the band's previous guitar players.[22]

Sykes was heavily involved in the making of Whitesnake's next album, co-writing nine songs with vocalist David Coverdale.[23] He began pushing the band towards a more mainstream sound,[24][25] which Coverdale described as "leaner, meaner and more electrifying".[26] The two began writing together in the South of France in early 1985, before heading to Little Mountain Sound Studios in Vancouver to begin recording.[27] During that time, however, Coverdale's relationship with the rest of the band began to sour with him eventually firing all other members of the group, including Sykes.[6][23] Whitesnake's seventh album was eventually released in April 1987, and it became the band's most commercially successful album to date, reaching number two on the Billboard 200 chart and selling over eight million copies in the US.[28][29]

Since leaving Whitesnake, Sykes's relationship with David Coverdale has remained strained, with Sykes admitting he's still "very bitter" about how Coverdale handled his firing.[23] In the early 2000s, there was a "reaching out" between the two as Coverdale was putting together a new Whitesnake line-up. By his own account, Sykes recommended Marco Mendoza and Tommy Aldridge for the band (both of whom would end up joining), after which he never heard from Coverdale again.[8] Conversely, Mendoza claimed to have acted as a mediator of sorts between the two.[30] Coverdale admitted to having spoken to Sykes about a possible reunion, but ultimately felt that the two had been "their own bosses" for too long.[31] In 2017, Sykes said of Coverdale: "I really have no interest in ever talking to him again."[23]

Blue Murder[edit]

Following his dismissal from Whitesnake, Sykes formed Blue Murder, which featured bassist Tony Franklin and drummer Carmine Appice.[32][33] Initially, drummer Cozy Powell and vocalist Ray Gillen were tapped for the project. Powell eventually left to join Black Sabbath, while Gillen was let go after Geffen Records' A&R executive John Kalodner encouraged Sykes to front the band himself.[6][18][34]

Blue Murder's self-titled debut album was released in April 1989, and it reached number 69 on the Billboard 200 chart.[35] The band then embarked on a tour across America and Japan.[33][36] While their debut album would go on to sell an estimated 500,000 copies according to Sykes, Blue Murder's success fell short of expectations.[18][33][37] Sykes felt Geffen Records did not properly promote the group, stating: "I think they were trying to get me and David [Coverdale] back together. They wanted me to get back with the 'winning formula'. But the wounds were too fresh. I stayed with the same label. In hindsight, I would have done better with a different label."[6][18] During the recording of their sophomore effort, Franklin and Appice left Blue Murder, while Sykes put together a new line-up.[33] At the same time, Sykes was being considered for the guitarist spot in Def Leppard. While no formal auditions took place, Sykes did jam with the group and sang backing vocals on their 1992 album Adrenalize. Ultimately the band would hire Vivian Campbell, formerly of Dio (and Sykes's successor in Whitesnake).[38] Blue Murder, meanwhile, released their second album Nothin' But Trouble in 1993. It failed to chart, something Sykes once again attributed to Geffen Records, whom he felt "didn't do anything" to promote the record.[6] In 1994, Blue Murder released a live album, Screaming Blue Murder: Dedicated to Phil Lynott, after which the band were dropped from their label and broke up.[18]

There have been several attempts to reunite Blue Murder since the band's breakup. In 2019, Carmine Appice revealed that the group had rehearsed together, but Sykes wanted the band to tour under the moniker John Sykes & Blue Murder, something Appice was unwilling to do.[39] In 2020, Appice stated that he and Sykes had once again talked about the possibility of a Blue Murder reunion, but nothing ultimately came of the conversation.[40]

Solo career[edit]

After parting ways with Geffen Records, Sykes signed with the Japanese branch of Mercury Records and released his first solo album Out of My Tree in 1995.[18] Sykes released his second solo album Loveland in 1997. Mercury Records had initially requested a seven-track extended play of ballads, but Sykes ultimately decided to expand the project into a proper album. That same year he released 20th Century, a companion album to Loveland featuring heavier material.[18] In 2000, Sykes released Nuclear Cowboy.[34] After a failed attempt to secure a European record deal with Z Records, Sykes signed a distribution deal with Burnside Distribution in 2003, which made his solo albums available in the US for the first time.[41][42] In 2005, Sykes released Bad Boy Live!, a live album featuring songs from his time with Whitesnake, Thin Lizzy and Blue Murder, as well his solo material.[43] According to a 2021 interview with guitarist Richard Fortus, Sykes auditioned for Guns N' Roses in 2009.[44]

During an appearance on That Metal Show in 2011, Sykes revealed he was forming a new band with drummer Mike Portnoy.[45] However, Eddie Trunk confirmed in 2012 that the project, tentatively named "Bad Apple", was no longer moving forward. Bassist Billy Sheehan had been tapped to the band as well, but ultimately the individual schedules of all parties involved didn't line up. According to Trunk, Sykes was "not on the same timetable" as the others.[46] Sykes was later replaced by Richie Kotzen and group became The Winery Dogs.[47]

In 2013, Sykes revealed he was working on a new solo album.[48] Samples from the record were released in 2014 and Sykes discussed the album in a 2017 interview with Young Guitar Magazine.[49][50] In January 2019, it was announced that Sykes had signed a recording contract with Golden Robot Records with the intent of releasing his long-delayed album that same year. However, in November 2019, Sykes announced that he had ended his partnership with Golden Robot Records.[51] On 1 January 2021, Sykes released "Dawning of a Brand New Day", his first new song in over twenty years.[52] This was followed up by "Out Alive" in July.[53]

Personal life[edit]

Sykes married Jennifer Brooks-Sykes on 10 April 1989, after four years of living together.[54] They were married until 1999.[citation needed] Sykes has three sons; James, John Jr. and Sean.[54][55][56]

Style and influences[edit]

Sykes has listed Jimmy Page, Ritchie Blackmore, Gary Moore, Michael Schenker, Uli Jon Roth, Allan Holdsworth and John McLaughlin among his biggest influences as a guitar player.[43][54] He regards himself as a "blues player that plays rock".[8] Some of the main characteristics of Sykes's playing are his fast alternate picking, doubled‐note lines, wide fret-hand vibrato, pinch harmonics and tapping.[57][58][59] He has also been described as having a great sense of melody in his playing.[60][61] In 2004, Sykes was included on Guitar World's list of the "100 Greatest Heavy Metal Guitarists of All Time".[62] In 2011, he was included on Guitar Player's list of "50 Unsung Heroes of the Guitar".[63] Guitar Player also highlighted Sykes in their 2021 article "How '80s Guitar Heroes Changed Hard Rock Forever" as one of the quintessential hard rock guitarists of the 1980s.[59]

Equipment[edit]

Sykes has used a 1978 Gibson Les Paul Custom throughout most of his career. The guitar is fitted with chrome hardware (which were added at Phil Lynott's suggestion), Grover tuners and a brass nut. The guitar featured a Gibson Dirty Fingers pick-up in the bridge position, that was later swapped out for a Gibson PAF reissue.[64] In 2006, Gibson produced a limited number of Les Pauls based on Sykes's model. The line quickly sold out.[10] Other guitars Sykes has used over the course of his career include a sunburst 1959 Gibson Les Paul (which is featured on the cover of his 1997 album Loveland), a 1961 Fender Stratocaster, an EVH Frankenstein and a Joe Satriani model Ibanez. Sykes uses Ernie Ball strings, gauge .010 to .046, and Dunlop 1.14mm Tortex picks.[64]

Sykes mainly uses EVH 5150 III amplifiers and cabinets. He previously used modified Marshall JCM800s for live performances. For Whitesnake's 1987 album and the first Blue Murder record, Sykes used two Mesa Boogie Coliseum heads with Mark III pre-amp sections and six 6L6 power tubes.[64] For live performances, Sykes has used rack‐mounted chorus and delay effects.[57] During his first stint with Thin Lizzy, Sykes used a Boss chorus pedal, which he retired after Whitesnake bassist Neil Murray complained it was too noisy.[4]

Discography[edit]

Solo albums[edit]

- Out of My Tree (1995)

- Loveland (1997)

- 20th Century (1997)

- Nuclear Cowboy (2000)

- Bad Boy Live! (2004)

with Tygers of Pan Tang[edit]

- Spellbound (1981)

- Crazy Nights (1981)

- The Cage (1982) (Tracks 8 and 10)

with Thin Lizzy[edit]

- Thunder and Lightning (1983)

- Life (1983)

- One Night Only (2000)

with Whitesnake[edit]

- Slide It In (1984) (US version)

- Whitesnake (1987)

with Blue Murder[edit]

- Blue Murder (1989)

- Nothin' but Trouble (1993)

- Screaming Blue Murder: Dedicated to Phil Lynott (1994)

Other appearances[edit]

| Year | Artist | Album | Track(s) | Credits | Ref(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1992 | Def Leppard | Adrenalize | — | Backing vocals | [38] |

| 1996 | Various artists | Crossfire: Salute to Stevie Ray | "Pride and Joy" | Guitar | [65] |

| 1998 | Various artists | Merry Axemas 2 – More Guitars for Christmas | "God Rest You Merry, Gentlemen" | Guitar, producer, mixer | [66] |

| 2001 | Phil Lynott | Live in Sweden 1983 | All tracks | Guitar, backing vocals | [67] |

| 2002 | Hughes Turner Project | HTP | "Heaven's Missing an Angel" | Guitar | [68] |

| 2004 | Derek Sherinian | Mythology | "God of War" | Guitar | [69] |

| 2016 | Rick Wakeman, Tony Ashton | Gastank | "Growing Up", "The Man's a Fool" | Guitar | [70] |

| 2018 | Various artists | Moore Blues for Gary: A Tribute to Gary Moore by Bob Daisley and Friends | "Still Got the Blues" | Guitar | [71] |

References[edit]

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ a b Ankeny, Jason. "John Sykes - Biography & History". AllMusic. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- ^ a b Johnson, Howard (26 August – 8 September 1982). "Tygers Bend the Bars". Kerrang!. No. 23. London, England: United Newspapers. pp. 24–26.

- ^ a b c Bowcott, Nick (31 March 1989). "Ex-Whitesnake John Sykes forms Blue Murder". Circus. New York: Circus Enterprises Corporation. p. 89.

- ^ a b c d Kay, Max (23 February – 7 March 1984). "Confident Lickster - Max Kay talks to new Whitesnake recruit John Sykes". Kerrang!. No. 62. London, England: United Newspapers.

- ^ Johnson, Howard (21 October – 3 November 1982). "Can this man get Lizzy Syke-d up?". Kerrang!. No. 27. London, England: United Newspapers. p. 40.

- ^ a b c d e f g "June 1999 Interview with Tony Nobles from Vintage Guitar magazine". John Sykes. 27 March 2008. Archived from the original on 27 March 2008. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- ^ Guy, Lyn (15 July 1989). "Slo an' Easy". Kerrang!. No. 247. London, England: United Newspapers. p. 31.

- ^ a b c d e Syrjälä, Marko (7 September 2008). "John Sykes - Thin Lizzy, ex-Whitesnake, Blue Murder, Tygers of Pan Tang". Metal-Rules.com. Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- ^ a b c Dome, Malcolm (February–March 2019). "Thunder and Lightning - The Last Days of Thin Lizzy". Rock Candy. No. 12. London, England: Rock Candy Magazine Limited. pp. 28–32.

- ^ a b c "Biography". John Sykes. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- ^ Brooks 2000, p. 19.

- ^ Byrne 2004, p. 21.

- ^ Putterford 1994, p. 41.

- ^ Byrne 2004, p. 164.

- ^ Brooks 2000, p. 114.

- ^ Byrne 2004, p. 202.

- ^ Byrne 2004, p. 214.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Interview with John Sykes, July 1999". Melodic Rock. Archived from the original on 19 April 2019. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- ^ "Ex-Thin Lizzy Guitarist John Sykes Featured On Metal Express Radio This Thursday". Brave Words & Bloody Knuckles. 26 July 2009. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- ^ Dome, Malcolm (9–22 February 1984). "John Sykes". Kerrang!. No. 61. London, England: United Newspapers.

- ^ Gilmour, Hugh (2017). Whitesnake (booklet). Whitesnake. Parlophone Records Ltd. pp. 5–9. 0190295785192.

- ^ Popoff 2015, pp. 107–109.

- ^ a b c d "Whitesnake – Guitarist John Sykes Discusses David Coverdale – "I Have No Interest In Ever Talking To Him Again"". Brave Words & Bloody Knuckles. 7 June 2017. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- ^ Suter, Paul (19 April 1989). "Fatal Attraction". Raw. No. 17. London, England: EMAP Publishing Limited. pp. 50–53.

- ^ Dome, Malcolm (June–July 2017). "John Sykes - Strife in the Studio". Rock Candy. No. 2. London, England: Rock Candy Magazine Limited. pp. 36–39.

- ^ Lawson, Dom (29 July 2009). "Whitesnake: The Story Behind 1987". Metal Hammer. Louder. Retrieved 9 March 2021.

- ^ Wall 2010.

- ^ "Billboard 200 - The Week of June 13, 1987". Billboard. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- ^ "RIAA Searchable Database: search for Whitesnake". Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- ^ Mosqueda, Ruben (29 December 2010). "Marco Mendoza Interview". Sleaze Roxx. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- ^ Chirazi, Steffan (March 2011). "David Coverdale Q&A". Classic Rock presents: Whitesnake - Forevermore (The Official Album Magazine). London: Future plc. Retrieved 12 August 2021.

- ^ Larkin 1995, p. 59.

- ^ a b c d "Tony Franklin, Carmine Appice & Eric Blair talk John Sykes 2020". YouTube. blairingoutshow. 26 January 2020. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- ^ a b "2001 Interview with Troy Wells of ballbusterhardmusic.com". John Sykes. Archived from the original on 19 December 2009.

- ^ "Billboard 200 Chart - Week of June 24, 1989". Billboard. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- ^ "Carmine Appice - The full in bloom Interview - Guitar Zeus, Vanilla Fudge, Ozzy, Book, Blue Murder". YouTube. full in bloom. 11 November 2019. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- ^ "Blue Murder Bassist Talks John Sykes, the Breakup & Whitesnake". YouTube. full in bloom. 4 February 2020. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- ^ a b Elliott, Paul (6 March 2018). "Def Leppard look back on how they made 90s rock classic Adrenalize". Classic Rock. Louder. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- ^ "Carmine Appice Talks Aborted Blue Murder Reunion - "I Don't Need To Go Out And Play Under John Sykes As John Sykes & Blue Murder"". Brave Words & Bloody Knuckles. 30 November 2019. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- ^ "Carmine Appice On Why Blue Murder Reunion Hasn't Happened Yet: We Still Can't Get John Sykes Out Of The House". Blabbermouth.net. 29 January 2020. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- ^ "John Sykes Issues Statement Regarding Failed Z Records Deal". Blabbermouth.net. 7 January 2003. Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- ^ "John Sykes Signs U.S. Distribution Deal". Blabbermouth.net. 6 March 2003. Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- ^ a b "Bad Boys Running Wild: Interview with John Sykes". John Sykes. Archived from the original on 10 April 2008. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- ^ "John Sykes Auditioned For Guns N' Rosees In 2009: 'It Was Incredible,' Says Richard Fortus". Blabbermouth.net. 30 January 2021. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- ^ "Mike Portnoy, John Sykes Join Forces In New Project". Blabbermouth.net. 25 July 2011. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- ^ "Sykes/Portnoy band ends, the story". Eddie Trunk. 24 January 2012. Archived from the original on 27 January 2012. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- ^ "Portnoy, Kotzen, Sheehan Project Gets Name; Debut Album Due In May". Blabbermouth.net. 22 March 2013. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- ^ "John Sykes – Fifth Studio Album Due In 2013". Brave Words & Bloody Knuckles. 4 February 2013. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- ^ "New Track Samples". John Sykes. 25 December 2014. Archived from the original on 6 February 2015. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- ^ "Young Guitar 2017年4月号:特集 ジョン・サイクス". Shinko Music Entertainment. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- ^ "Legendary Guitarist John Sykes Splits With Golden Robot Records Without Releasing Long-Awaited New Album". Blabbermouth.net. 17 November 2019. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- ^ "Legendary Guitarist John Sykes Releases Music Video For New Single 'Dawning Of A Brand New Day'". Blabbermouth.net. 1 January 2021. Retrieved 1 January 2021.

- ^ "Legendary Guitarist John Sykes Releases Music Video For New Single 'Out Alive'". Blabbermouth.net. 4 July 2021. Retrieved 4 July 2021.

- ^ a b c Miller, Geri (May 1989). "John Sykes - Blue Murder's Axe Killer". Metal Edge. New York: Zenbu Media. p. 82.

- ^ "Thin Lizzy guitarist John Sykes's son playing keyboards in Statius". Brave Words & Bloody Knuckles. 18 February 2008. Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- ^ Bad Boy Live! (booklet). John Sykes. Victor. 2004. VICP-62956.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ a b Hilborne, Phil (30 September 2019). "5 guitar tricks you can learn from Whitesnake's John Sykes". MusicRadar. Retrieved 6 January 2021.

- ^ "The Top 10 Pick Squealers of All Time". Guitar World. 27 October 2017. Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- ^ a b "They Came From Planet Shred: How '80s Guitar Heroes Changed Hard Rock Forever". Guitar Player. 9 March 2021. Retrieved 9 March 2021.

- ^ Wallner, Will (21 December 2012). "Bent Out of Shape: John Sykes is Back!". Guitar World. Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- ^ Wallner, Will (29 April 2013). "Bent Out of Shape: Blue Murder Remastered and Reloaded". Guitar World. Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- ^ "Guitar World's 100 Greatest Heavy Metal Guitarists Of All Time". Blabbermouth.net. 23 January 2004. Retrieved 6 January 2021.

- ^ Molenda 2011.

- ^ a b c "Equipment". John Sykes. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- ^ "Various Artists – Crossfire: Salute to Stevie Ray". AllMusic. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- ^ "Various Artists – Merry Axemas, Vol. 2: More Guitars for Christmas". AllMusic. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- ^ "Phil Lynott – Live in Sweden 1983". AllMusic. Retrieved 4 January 2021.

- ^ "Hughes-Turner Project – Hughes-Turner Project". AllMusic. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- ^ "Derek Sherinian – Mythology". AllMusic. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- ^ "Rick Wakeman / Tony Ashton – Gastank". AllMusic. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ Lewry, Fraser (6 December 2018). "The story behind this year's all-star tribute to Gary Moore album". Classic Rock. Louder. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

Book sources[edit]

- Brooks, Ken (2000). Phil Lynott & Thin Lizzy: Rockin' Vagabond. Agenda. ISBN 978-1-899-88221-2.

- Byrne, Alan (2004). Thin Lizzy: Soldiers of Fortune. Firefly. ISBN 978-0-946719-57-0.

- Putterford, Mark (1994). Philip Lynott: The Rocker. Castle Communications. ISBN 1-898141-50-9.

- Larkin, Colin (1995). The Guinness Who's Who of Heavy Metal (Second ed.). Guinness Publishing. ISBN 0-85112-656-1.

- Molenda, Michael (2011). Guitar Player Presents 50 Unsung Heroes of the Guitar. Backbeat Books. ISBN 978-1-617-13021-2.

- Popoff, Martin (2015). Sail Away: Whitesnake's Fantastic Voyage. Soundcheck Books LLP. ISBN 978-0-9575-7008-5.

- Wall, Mick (2010). Appetite for Destruction: The Mick Wall Interviews. Hachette UK. ISBN 978-1-409-11435-2.

External links[edit]

- 1959 births

- Living people

- 20th-century British guitarists

- 21st-century British guitarists

- English rock guitarists

- English heavy metal guitarists

- English rock singers

- English heavy metal singers

- Thin Lizzy members

- Whitesnake members

- Blue Murder (band) members

- Badlands (UK band) members

- Musicians from Reading, Berkshire

- British lead guitarists