The Time Machine (2002 film)

| The Time Machine | |

|---|---|

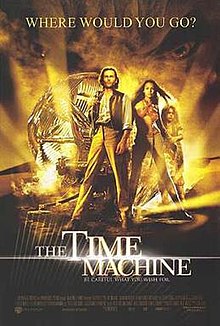

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Simon Wells |

| Screenplay by | John Logan |

| Based on |

|

| Produced by | |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Donald McAlpine |

| Edited by | Wayne Wahrman |

| Music by | Klaus Badelt |

Production company | |

| Distributed by |

|

Release date |

|

Running time | 96 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $80 million[2] |

| Box office | $123.7 million[2] |

The Time Machine is a 2002 American post-apocalyptic science fiction film loosely adapted by John Logan from the 1895 novel of the same name by H. G. Wells and the screenplay of the 1960 film of the same name by David Duncan. Arnold Leibovit served as executive producer and Simon Wells, the great-grandson of the original author, served as director. The film stars Guy Pearce, Orlando Jones, Samantha Mumba, Mark Addy, and Jeremy Irons, and includes a cameo by Alan Young, who also appeared in the 1960 film adaptation. The film is set in New York City instead of London, and contains new story elements not present in the original novel or the 1960 film adaptation, including a romantic subplot, a new scenario about how civilization was destroyed, and several new characters such as an artificially intelligent hologram and a Morlock leader.

The film received generally negative reviews from critics and grossed $123 million worldwide. It was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Makeup (John M. Elliot Jr. and Barbara Lorenz) at the 75th Academy Awards, but lost to Frida.

Plot[edit]

In 1899, Dr. Alexander Hartdegen is an inventor teaching at Columbia University in New York. Unlike his friend David Philby, Alexander would rather do pure research than work in the world of business. After a mugger kills his fiancée Emma, he devotes himself to building a time machine that will allow him to travel back in time to save her. After completing the machine in 1903, he travels back to 1899 and prevents her murder, only to see her killed again when a carriage frightens the horses of another vehicle.

Alexander realizes that any attempt to save Emma will result in her death through other circumstances. He travels to 2030 to discover whether science has discovered how to change the past. At the New York Public Library, holographic librarian Vox 114 insists time travel to the past is impossible. Alexander travels to 2037, when the accidental destruction of the Moon by lunar colonists has begun rendering the Earth virtually uninhabitable. While restarting the machine, he is knocked unconscious by debris and travels forward 800,000 years to the date 16 July 802,701 before reawakening.

The Earth has healed, and the human race has reverted to a primitive lifestyle. Some survivors, called "Eloi", live on the sides of cliffs of what was once Manhattan. Alexander is nursed back to health by a woman named Mara, one of the few Eloi who speak English. He observes the broken moon and realizes that maybe his teachings led to this future just like Philby said. One night, Alexander and Mara's younger brother, Kalen, dream of a jagged-toothed face and a creature calling their name. Alexander informs Mara of the dream, and she tells him they all have that dream. She then notices that his watch is missing. The next day, the Eloi are attacked and Mara is dragged underground by ape-like creatures. They are called "Morlocks," and they hunt the Eloi. In order to rescue Mara, Kalen leads Alexander to Vox 114, which is still functional after 800,000 years.

After learning from Vox how to find the Morlocks, Alexander enters their underground lair through an opening that resembles the face in his nightmare. He is captured and thrown into an area where Mara sits in a cage. Alexander meets an intelligent, humanoid Über-Morlock, who explains that Morlocks descend from the humans who went underground after the Moon broke apart, while the Eloi evolved from those who remained on the surface. The Über-Morlocks are a caste of telepaths who rule the other Morlocks, who use the Eloi as food and breeding vessels.

The Über-Morlock explains that Alexander cannot alter Emma's fate; her death is what drove him to build the time machine in the first place, therefore saving her would be an impossibility due to temporal paradox. The Über-Morlock shows Alexander the time machine and tells him to go home. Alexander gets into the machine but pulls the Über-Morlock in with him, carrying them into the future as they fight. The Über-Morlock dies by rapidly aging when Alexander pushes him outside of the machine's temporal bubble. Alexander stops in 635,427,810, revealing a harsh, rust-colored sky over a wasteland of Morlock caves.

Accepting that he cannot save Emma, Alexander travels back to rescue Mara. After freeing her, he starts the machine and jams its gears, creating a distortion in time. Pursued by the Morlocks, Alexander and Mara escape to the surface as the time distortion explodes, killing the Morlocks and destroying their caves along with the time machine. Alexander begins a new life with Mara and the Eloi, while Vox 114 helps him educate them.

In 1903, Philby and Mrs. Watchit, Alexander's housekeeper, discuss his absence in his laboratory. Philby tells Mrs. Watchit he is glad that Alexander has gone to a place where he can find peace, and he would like to hire her as a housekeeper. She accepts until Alexander returns. Mrs. Watchit bids Alexander farewell, and Philby leaves, looking toward the laboratory affectionately; then proudly throws his bowler hat away in tribute to Alexander's objection to blind conformity.

Cast[edit]

- Guy Pearce as Dr. Alexander Hartdegen, associate professor of applied mechanics and engineering at Columbia University. In the novel, the time traveler's name isn't given.[3]

- Samantha Mumba as Mara, a virtuous Eloi woman who befriends Alexander and eventually becomes his love interest.

- Orlando Jones as Vox 114, a holographic artificial intelligence librarian at the New York Public Library in the future, who befriends Alexander.

- Mark Addy as David Philby, Alexander's good friend and conservative colleague.

- Jeremy Irons as The Über-Morlock, the leader of the Morlocks and a member of the telepathic-ruling caste of the Morlock world.

- Sienna Guillory as Emma, Alexander's fiancée.

- Phyllida Law as Mrs. Watchit, Alexander's housekeeper in New York.

- Alan Young as Flower store worker

- Omero Mumba as Kalen, Mara's young brother.

- Yancey Arias as Toren

- Laura Kirk as Flower seller

- Josh Stamberg as Motorist

- Myndy Crist as Jogger

- Connie Ray as field trip teacher

- Peter Karika as The Trainer

- John W. Momrow as Fifth Avenue carriage driver

- Max Baker as Mugger who kills Emma

- Jeffrey M. Meyer as Central Park carriage driver

- Raymond Hoffman as Central Park ice skater

- Richard Cetrone cameos as a Hunter Morlock.

- Doug Jones cameos as a Spy Morlock.

Production[edit]

The film was a co-production of DreamWorks and Warner Bros. in association with Arnold Leibovit Entertainment who obtained the rights to the George Pal original Time Machine 1960 and collectively negotiated the deal that made it possible for both DreamWorks and Warner Bros. to make the movie. Leibovit was interested in making a new film since the 1980s.[4]

Originally, Steven Spielberg was set to direct, but moved on to other projects. Then Brad Silberling took over, but left over creative differences.[5] Simon Wells, who had been directing animated films Spielberg has produced since An American Tail: Fievel Goes West, was interested in getting into live action. So he went to Jeffrey Katzenberg saying “I really ought to be directing this because, you know, the name!.”[6] Despite having never directed a live action movie before, producers Walter F. Parkes and Laurie MacDonald recognized that because of his animation background, the extensive visual effects work on the film wasn't going to be hard for him to handle.[7]

Director Gore Verbinski was brought in to take over the last 18 days of shooting, as Wells was suffering from "extreme exhaustion." Wells returned for post-production.[8] Filming began in February 2001 and finished on May 29, 2001.[9]

Special effects[edit]

The Morlocks were depicted using actors in costumes wearing animatronic masks created by Stan Winston Studio. For scenes in which they run on all fours faster than humanly possible, Industrial Light & Magic created CGI versions of the creatures.[10]

Many of the time traveling scenes were entirely computer generated, including a 33-second shot in the workshop where the time machine is located. The camera pulls out, traveling through New York City and then into space, past the ISS, and ends with a space plane landing at the Moon to reveal Earth's future lunar colonies. Plants and buildings are shown springing up and then being replaced by new growth in a constant cycle. In later shots, the effects team used an erosion algorithm to digitally simulate the Earth's landscape changing through the centuries.[10]

For some of the lighting effects used for the digital time bubble around the time machine, ILM developed an extended-range color format, which they named rgbe (red, green, blue, and an exponent channel) (See Paul E. Debevec and Jitendra Malik, "Recovering High Dynamic Range Radiance Maps from Photographs, Siggraph Proceedings, 1997).[10]

The film's original release date was December 2001, but it was moved to March 2002 because they wanted to avoid competition with The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring and also a scene was removed from the Moon destruction sequence showing pieces of the Moon crashing into buildings in New York because it looked too similar visually to the September 11 attacks.[11]

Soundtrack[edit]

A full score was written by Klaus Badelt, with the recognizable theme being the track "I Don't Belong Here", which was later used in the 2008 Discovery Channel Mini series When We Left Earth.[12]

In 2002, the film's soundtrack won the World Soundtrack Award for Discovery of the Year.

Reception[edit]

Box office[edit]

The film grossed $22 million at #1 during the opening weekend of March 8–10, 2002.[13] The film eventually earned $56 million in North America and $123 million worldwide.

Critical reaction[edit]

The film holds a 28% rating on Rotten Tomatoes based on 156 reviews with an average rating of 4.79/10. The site's critical consensus reads "This Machine has all the razzle-dazzles of modern special effects, but the movie takes a turn for the worst when it switches from a story about lost love to a confusing action-thriller."[14] Metacritic assigned the film a weighted average score of 42 out of 100, based on 33 critics, indicating "mixed or average reviews".[15] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "C+" on an A+ to F scale.[16]

William Arnold of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, who was somewhat positive about the film, wrote that it lost some of the simplicity and charm of the 1960 George Pal film by adding characters such as Jeremy Irons' "über-morlock". He praised actor Guy Pearce's "more eccentric" time traveler and his transition from an awkward intellectual to a man of action.[17] Victoria Alexander of Filmsinreview.com wrote that "The Time Machine is a loopy love story with good special effects but a storyline that's logically incomprehensible,"[18] noting some "plot holes" having to deal with Hartdegen and his machine's cause-and-effect relationship with the outcome of the future. Jay Carr of the Boston Globe wrote: "The truth is that Wells wasn't that penetrating a writer when it came to probing character or the human heart. His speculations and gimmicks were what propelled his books. The film, given the chance to deepen its source, instead falls back on its gadgets."[19]

Some critics praised the special effects, declaring the film visually impressive and colorful, while others thought the effects were poor. Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times scorned the film, and found the Morlock animation cartoonish and unrealistic, because of their manner of leaping and running.[20] Ebert notes the contrast in terms of the social/racial representation of the attractive Eloi between the two films, between the "dusky sun people" of this version and the Nordic race in the George Pal film. Aside from its vision of the future, the film's recreation of New York at the turn of the century won it some praise. Bruce Westbrook of the Houston Chronicle writes "The far future may be awesome to consider, but from period detail to matters of the heart, this film is most transporting when it stays put in the past."[21]

In the years since, Simon Wells admitted that while he was happy with how the movie itself came out in the end, there were elements about the story that really weren’t as satisfying as they should have been. "I was aware of that, while shooting, but unable to do anything about it."[22]

References[edit]

- ^ a b "The Time Machine". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. Retrieved July 10, 2017.

- ^ a b "The Time Machine (2002)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 2015-10-31.

- ^ "SparkNotes: The Time Machine: Characters". www.sparknotes.com.

- ^ Davidson, Paul (November 20, 2001). "Arnold Leibovit on The Time Machine and Time Travel". IGN. Retrieved November 26, 2023.

- ^ "The Stax Report: Script Review of The Time Machine". IGN. July 19, 2000. Retrieved November 26, 2023.

- ^ Spry, Jeff (May 10, 2022). "20 YEARS AGO, H.G. WELLS' GREAT-GRANDSON REIMAGINED A TIME TRAVEL CLASSIC". Inverse. Retrieved November 26, 2023.

- ^ "Simon Wells Talks Time Machine". IGN. July 25, 2001. Retrieved November 26, 2023.

- ^ "Time Machine director bows out". The Guardian. 2001-05-11. Archived from the original on 2022-12-07.

- ^ Filming Dates

- ^ a b c "About Time | Computer Graphics World". Cgw.com. 2002-03-03. Retrieved 2015-10-31.

- ^ Grunewald, Donna. "WTC in Movies". wtcinmovies.tripod.com. Archived from the original on 2018-07-23. Retrieved 2018-07-22.

- ^ "When We Left Earth: The NASA Missions" – via www.imdb.com.

- ^ Goodridge, Mike (March 11, 2002). "The Time Machine lands at number one". Screen Daily. Retrieved November 26, 2023.

- ^ "The Time Machine (2002)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 2019-07-23.

- ^ "The Time Machine". Metacritic.

- ^ "Home". CinemaScore. Retrieved 2023-01-01.

- ^ Arnold, William (2002-03-07). "Despite excesses, 'The Time Machine' cranks out an imaginative adventure". seattlepi.com. Retrieved 2015-10-31.

- ^ Alexander, Victoria (March 6, 2002). "The Time Machine (2002)". FilmsInReview.com. Archived from the original on 2009-07-19. Retrieved 2013-11-19. via RottenTomatoes.com.

- ^ "Entertainment". Boston.com. 2014-03-26. Retrieved 2015-10-31.

- ^ Ebert, Roger. "The Time Machine Movie Review (2002) | Roger Ebert". Rogerebert.suntimes.com. Archived from the original on 2012-06-14. Retrieved 2015-10-31.

- ^ Westbrook, Bruce (March 8, 2002). "Past works best for 'The Time Machine'". The Tuscaloosa News. The Houston Chronicle.

- ^ "Mars Needs Moms, but Earth needs Director Simon Wells! – Animated Views".

External links[edit]

- 2002 films

- 2000s dystopian films

- 2002 science fiction action films

- 2000s science fiction adventure films

- American science fiction action films

- American science fiction adventure films

- American alternate history films

- Remakes of American films

- The Time Machine

- DreamWorks Pictures films

- American dystopian films

- Fictional-language films

- Films about time travel

- Films based on science fiction novels

- Films based on works by H. G. Wells

- Films directed by Simon Wells

- Films postponed due to the September 11 attacks

- Films set in 1899

- Films set in 1903

- Films set in 2030

- Films set in 2037

- Films set in the future

- Films set in New York City

- Films shot in California

- Films shot in Los Angeles

- Films shot in New York (state)

- Films about holography

- Films about impact events

- Moon in film

- Warner Bros. films

- American post-apocalyptic films

- Films with screenplays by John Logan

- Films scored by Klaus Badelt

- Films produced by Walter F. Parkes

- Films produced by David Valdes

- Science fiction novels adapted into films

- 2000s English-language films

- 2000s American films