Wikimedia Deutschland/Decentralized Fundraising, Centralized Distribution

Decentralized Fundraising, Centralized Distribution

[edit]This paper is part of WMDEs activities to insert knowledge and good practices into the conversation and deliberation around creating a governance system for the movement. The content provided here is intended to support the work of the MCDC and the stakeholders it serves in creating the movement charter. The positions of WMDE related to movement governance are not included here.

This research reviews current practices in fundraising and funds distribution in eight international NGO confederations

Provided by Wikimedia Deutschland, September 2022

Author: Nikki Zeuner

Research Assistant: Hannah Winter

We would like to thank the staff of the eight international NGOs who shared their time, expertise and wisdom with our team for the purpose of this report.

Executive Summary

[edit]This paper, published in the context of the Wikimedia Movement’s deliberations around its Movement Charter and the implementation of 2030 Movement Strategy, provides an overview of financial practices of comparable large international nonprofit/nongovernmental organizations (INGOs) which are organized as confederations or networks.

Based on interviews and information sharing with staff of eight organizations, including Amnesty International, Oxfam International, CARE International, World YWCA, Greenpeace and the International Cooperative Alliance, the research asks about key practices in the areas of fundraising, decision-making about fund allocation, and in particular, about redistribution policies and mechanisms. This latter topic was given particular focus, because Movement Strategy emphasizes equity in funds distribution across an economically unequal international movement. Yet it leaves open how this should be structured.

The main findings of the research show that the Wikimedia Movement differs significantly in its practices from the screened organizations: All of the organizations are based on their affiliates fundraising independently, online and offline. In several cases the INGO specifically invests in the fundraising capacity of affiliates. Yet fundraising is highly strategic rather than diversified, in terms of markets, fundraising affiliates, and revenue sources.

With one exception, the international entity collects membership dues and is in part funded by them. The international entities have a diversity of roles, with acting as a secretariat and coordination being the most common ones. Only a minority of international entities engage in their own fundraising or fundraise for the movement. Notably, grantmaking from international entities to the affiliates is not a practice, and occurs only in few exceptions when there is third party program funding. Participation in funding decisions, which has been previously researched in a report commissioned by the MS 2030 Resource Allocation Working group[1], is practiced mostly through democratic and equitable governance and committee structures. While these structures vary greatly, both reports conclude that governance and funding systems are inseparably linked.

Finally, three of the organizations have distinct, policy-based, central funds redistribution mechanisms. These are discussed in some detail, in terms of their principles, formulas and review periods.

The results of this research can be summarized as follows: International NGO confederations practice decentralized fundraising, and those that redistribute funds for equity do so in a centralized manner, based on policies agreed upon by the democratic governance bodies of the confederation. The affiliates that fundraise in strong markets thus support the affiliates in smaller markets.

The research part concludes with a list of insights for the upcoming deliberations of the Wikimedia Movement. In the second part of the paper, readers can find a short history of Wikimedia revenues and resources, and an overview of the elements of 2030 Movement Strategy relevant to revenue generation and distribution. The appendices provide a list of guiding questions for the Movement deliberations to follow, and an overview of the structures of the INGOs in the sample.

Introduction

[edit]In 2022, 10 years have passed since the Board of the Wikimedia Foundation (WMF) changed the rules of fundraising and resource distribution for the Wikimedia Movement. Effectively, this created a situation in which affiliates, with very few exceptions, no longer actively fundraise in their countries, and all donations solicited through Wikimedia websites go directly to the WMF. Since then affiliates receive a share of funds raised by applying for grants from the WMF and are no longer directly supported by readers and small donors in their country. As a result, not only is the generation of funds centralized with the WMF, but also the decisions about how, where, according to which criteria and to what extent funds are spent.

What did the movement experience and learn in these 10 years of a centralized model? What has worked and what did not ?

The recommendations that were the result of the Movement Strategy process are an expression of the desire to reorganize how finances flow in and around the movement. Equity, subsidiarity of decision-making, people-centeredness, and decentralization are but a few of the core principles that have emerged. At the same time, necessities such as transparency, accountability to donors, protection of the trade marks, and responsible use of funds for the mission of the movement must be maintained.

The recommendations state:

In the near future, the Movement should play a guiding role in resource allocation. The processes for allocation should be designed through consultation and described in the Movement Charter. This transition to Movement-led guidance should occur in a timely fashion.

As a committee of Wikimedia community members embarks on drafting the Movement Charter, its members will have to consider not only the overall governance, but also revenue generation and resource allocation, in accordance with the Movement Strategy direction, recommendations and principles.

The committee is drafting also in the context of a quickly changing world with many challenges. Wikimedia is not operating alone in this world. This paper provides an overview of the related practices of allied, volunteer-based global movements - with the intention to inform the writing of the Movement Charter. Some of these movements have reformed both governance and resource policies in recent years to improve equitable distribution of resources. Some of their experiences will help the movement to determine what not to do.

This paper attempts to demonstrate some of the options, and, similar to our previous paper[2], introduce an empirical base and a joint language for further deliberation.

Part 1

[edit]Practices in Revenue Generation and Distribution

[edit]To provide factual information and a joint language for the discussion of future financial movement structures, WMDE conducted a study of existing practices in revenue generation and resource allocation in comparable international movements.

Methodology

[edit]For this empirical analysis, the team interviewed C-Level staff of eight international NGOs. The team applied the following criteria in selecting the INGOs:

- a global network or confederation of independent organizations

- connected by a global mission

Eight large and renowned INGOs from the areas of environment, human rights and humanitarian aid were included in the group. Five out of the eight interviewees represent INGO movements that, like Wikimedia, work with large volunteer bases. The volunteers provide activism, program work, fundraising and advocacy for the mission.

For the purposes of this paper, each INGO was anonymized, and the practices are summarized below.

The following questions were asked:

Governance

How is your confederation structured?

How is the board of the international entity constituted?

What types of affiliates do you have?

What is the division of labor among affiliates in your movement in terms of

- resource generation

- resource allocation

Fundraising/Revenue Generation

Do donations always go to a legal entity in the country of the donor?

Are there central functions for fundraising? To what extent is your fundraising centralized?

Are there standards and policies for affiliate fundraising? Do they include rules on revenue sources?

Is there a certification process/body for fundraising chapters?

Are there criteria such as ROI projections for allowing chapters to fundraise?

Resource Allocation/Redistribution

Do you redistribute funds across your movement/confederation?

According to which policy, process and formula?

What's the overall ratio of funds allocated for global north/ global south affiliates?

What's the overall ratio of funds allocated for international entity and affiliates?

How have these ratios changed over time?

How often is this (the policy and formula) reviewed and adapted?

Do you ensure participation of communities in fundraising and allocation decisions? if so, how?

Definitions

[edit]Affiliate - members, chapters, or sections

Allocation - any decision to move movement financial resources from one entity to another, or from one region to another

Fundraising - any activity designed to generate resources for a member or a confederation, and includes all revenue sources.

Grantmaking - an impermanent, transactional transfer of funds between a giving entity and a receiving entity based on a process that includes a proposal/application, a review/decision, as well as accountability through financial and impact reporting.

Home Donor Rule - a policy assuring that an affiliate has the first right of fundraising in its geographic area or country.

INGO or confederation - the sum of affiliates in the movement

International entity - the non-national or non-thematic organization with special responsibilities

Offices - non-independent branches of the international entity or the confederation

Redistribution - any permanent, policy-based mechanism designed to move financial resources from entities or geographic regions with high revenues to entities or geographic regions with lower revenues.

Results

[edit]Standards: Governance and Revenue Generation

[edit]Seven out of the eight INGOs have a global assembly, or a global affiliates body as the highest governance body (see also our governance paper). All of them have revenue structures based on affiliate in-country fundraising. All international entities serve as secretariats, as coordinating bodies and/or provide services to the members.

Beyond that, the sampled INGOs engage in a variety of practices related to governance, fundraising, and resource distribution as well as to role and size of the international organization vis-a-vis the local/national or regional member organizations. This report provides an overview of these practices.

Role of the International Entity v. Affiliates

[edit]The historical development of the confederations has led to their current configuration and division of labor in each case. It would go beyond the scope of this paper to consider all of these histories. It is however important to understand that in several cases, unlike as with Wikimedia, the formation of the international entity followed after several affiliates, including a major founding one, already existed. In those cases affiliates realized that for pursuing a global mission around human rights, humanitarian response, or environmental protection, global coordination was required. In only a few cases did the founding organization also become the international entity.

In most cases, the International entity does not act as a headquarters or central entity for the movement. Most of the interviewed leaders see their movements as networks of independent organizations. The term decentralized was used often to describe the confederation.

The international entity in the majority of the cases acts as a secretariat for the membership. Tasks of a secretariat include supporting the global assembly and board in policy, strategy and decision making. In many cases the international entity acts as a service provider to the members. In these cases they offer a few functions, such as program coordination, back office services, maintaining joint software platforms, advocacy with international bodies, or capacity building. Rarely do they offer all of these functions. In some cases, the Secretariat also provides a leadership role in terms of strategy and program priorities.

Only in a few cases does the international entity engage in fundraising on behalf of the confederation. In most cases, this was not the norm, and exceptions to it were clearly identified as such and had to be justified on a case by case basis, working with the affiliate in the country of the donor.

Three INGOs fill the role of managing a fund redistribution mechanism, which is described in more detail below.

Funding of the International Entity

[edit]There are two cases of traditional grassroots democracy, both are large global associations formed in the late 1800s with hundreds of member affiliates. In these cases, the role of the international entity is a service provider, with direct accountability to the members and completely dependent on the decisions of the membership or their governing bodies. Funding for the international entity in these cases also comes to a large percentage from membership dues, mirroring the accountability financially.

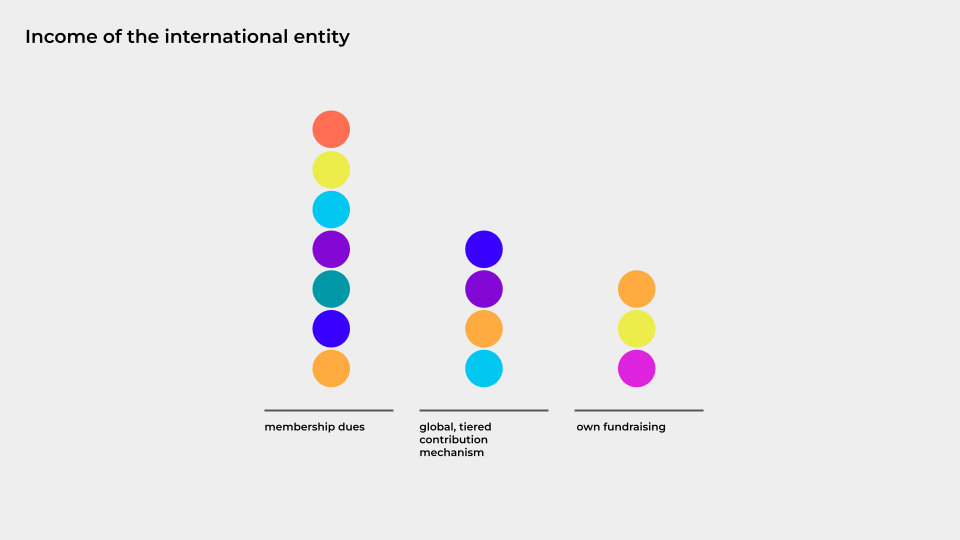

With one exception, all international entities in our sample are funded through membership dues, fees or levies.

A few international entities are funded through a mix of revenue sources. Only three of them engage in their own direct fundraising for the entity.

Affiliate Fundraising

[edit]All eight of the INGO federations from our sample are based on a revenue model in which each member or affiliate organization has the discretion to engage in fundraising in their country or region. Donors are able to receive tax deductions based on donating to a domestic organization. In some cases, affiliates were founded specifically to access a fundraising market. Often the home rule applies as a default, meaning that affiliates from other countries or the international entity are prohibited from fundraising in a country with a domestic or regional affiliate. Home rule is frequently relinquished when it makes sense from a pragmatic perspective of receiving funds from an institutional donor as part of a consortium.

Affiliates are able to engage in all types of fundraising, from soliciting street donations, to major donors, legacies, to online fundraising. They each maintain their own donor data. Not one of the screened INGOs has centralized fundraising and/or traditional grantmaking as practices as a base for resource distribution. Fundraising is seen, besides as an income source, as an essential part of the public engagement strategy, globally and domestically, to keep a presence in the minds of people.

Several confederations maintain fundraising policies or codes. Some of these have restrictions on revenue sources, due to their mission and nature of their work - i.e. they do not accept donations from governments or corporations or both, so they can maintain independence. Three INGOs, much like Wikimedia, have individual small donations as their main or only source of income.

Revenue diversification is not seen as an end-all. Rather, the more mature organizations have focused on the revenue markets where their strengths lie. Two of them have strong risk management systems and staff, early detecting and addressing risks to revenue generation that come from affiliates or the donor markets.

Three of the interviewed organizations shared the experience that universal fundraising rules are difficult to apply equally in all countries and markets. As a result, fundraising policies tend to be non-existent, or if they do exist, they are broad and leave room for contextualization and adaptation. These policies are reviewed every few years to adapt to changing realities in the fundraising markets.

Three organizations have affiliate agreements that include some language on fundraising. Two INGOs or their international entities regularly review affiliate status for re-certification. Only one organization has an actual certification process for affiliates to fundraise, including minimum requirements for, and accountability around the return on investment (RoI) for fundraising activities. Others do consider RoI as a metric for fundraising, but in a less restrictive and formalized manner.

One INGO has a fundraising investment fund, financed out of the general member contribution fund. It strategically invests in the fundraising capacity of affiliates in promising markets. The goal is to increase the number of financially independent contributing members vs. the number of members that receive funds out of the general fund.

Redistribution

[edit]Only one INGO in the sample did not have a membership fee. In the traditional associations a classic membership fee applies based on the income of the members, and in one case combined with a comparison GDP formula of the member country. The contribution formula is periodically reviewed and adjusted. The member fees are then used for a variety of purposes:

In addition to the fees, in three of the eight cases, a global fund is generated specifically by the higher-income affiliates contributing revenue into a joint fund.

In one case this is a percentage of their unrestricted income. In another, the percentage increases with a larger income, after a series of significant deductions are made for fundraising costs, core costs and restricted income. In the third case, the contributing affiliates get to decide on and then commit in writing to their contribution ratio, i.e. the ratio between what they fundraise and what they are contributing to the joint fund.

These three organizations in our sample have explicit, complex policies around redistributing these funds to lower-income affiliates. Both contribution and redistribution happens based on a set of principles. These include solidarity, mutualizing risk, adaptability and transparency. The mechanisms as well as formulas are periodically reviewed and adjusted, with the periods being between two and four years. The review and renegotiation includes the relevant stakeholders, with typically the secretariat supporting the process or suggesting policy. The final body approving changes to the mechanism and the policy/agreement is in all cases the General Assembly, the highest decision making body.

In one of the three cases, the redistributed funds go mostly towards advocacy of the lower-income affiliates, as policy work is more difficult to fundraise for than service delivery or project work. In the other two cases, redistributed funds are allocated towards general operating expenses of the affiliates in need. Separate funding pots go towards building capacity for fundraising of affiliates in promising markets.

The organizations active in development aid and/or humanitarian work often do not have these policies, as they are structured to raise funds in the global north to be spent in the global south, to begin with. The way funds are allocated in these cases varies greatly, depending on the nature of the confederation. Often there are national or regional offices, or operational offices, who typically have their own leadership and governance. They in turn are funded by either a group of Global North offices or the joint fund. The respective budgets for the ‘implementing’ offices are based on the need in the individual countries (especially with humanitarian crisis response), their strategic plans, often developed with stakeholder engagement, and the specific work they are planning to do within the global strategy and coordinated agenda.

Finally, there are confederations in which a more indirect redistribution occurs through the services provided by the international entity. These services are in effect paid for by the higher-income affiliates and benefit all, including the lower-income ones. They may include capacity building, advocacy and back-office functions.

Affiliates, local offices and partners

[edit]The surveyed INGOs each had an affiliate system based on their historical development and requirements for realizing their mission-based work. Somewhat related to the discussion on hubs in the Wikimedia Movement, there are regional and thematic offices, which in many cases are not independent affiliates but rather implementing offices of other affiliates. In the case of associations, members are a particular type of organization or an association themselves.

A hotly debated issue in the international development sector is the extent to which funded and implementing organizations need to be certified members/affiliates or whether funding also should be extended to local, pre-existing CSOs. This localization debate is important for the Wikimedia movement to consider as it structures hubs and partnerships, in order not to repeat mistakes the development sector has already learned from and is now developing solutions for[3]. It is also interesting to notice that some of the interviewees were critical of regionalization, as it creates more layers of bureaucracy and politics, and complicates lines of communication between members and the secretariat.

Participation in Decision-Making about Use of Funds

[edit]The sampled INGOs, due to their governance models based on membership, have a variety of built in mechanisms that provide opportunities for participatory decision making. In many cases, at the highest level, the general assembly (GA) approves the budget of the international entity. The GA and/or its committees also review and adapt policies and agreements, including those regulating fundraising, resource allocation and redistribution. Recent governance reforms have sought to include more stakeholders from outside the network, departing from the classic membership model at both the general assembly and committee levels.

At the national and local level, due to the fact that all affiliates are eligible to fundraise, they also make independent decisions about how to spend their revenue, within the constraints of joint strategy and joint policies. This is probably the most clear distinction from how the Wikimedia Movement operates in terms of local participation in funds allocation. There are no members which are wholly financially dependent on the international entity.

At the community and/or beneficiary level, practices are less clear. The research did not identify an organization that has found an efficient or satisfactory model or practice through advisory boards or regional/national committees. But this is not felt as a major problem, due to the fact that affiliates are generally independent organizations complying with the charitable laws in their home countries, which include in most cases at a minimum a community-based board, at a maximum a membership based governance model. This assures a base level of community participation.

In the three cases with mature and permanent redistribution models, members who are recipients of funds have to comply with accountability mechanisms that are not unlike those used in grantmaking, including setting goals and reporting back on outputs and budgets. However, the international entity does not act like a grantmaker, but rather as an administrator of the contribution/redistribution mechanism.

Many of the organizations from the humanitarian and development aid sector struggle with legitimacy questions that are directly related to the way they raise and allocate funds. There is a growing perception that donors should directly fund local civil society organizations, rather than INGOs (see above on localization debate). This, so the demand, would de-colonize the aid system and put more power into the hands of people affected by the funded programs[4]. Some of the INGOs are starting to respond to this by loosening their affiliate rules, and funding partners, rather than turning every partner into a branded affiliate.

In some of these cases, as discussed above, regional offices, or implementing offices coordinate the disbursement of funds and the implementation of programs. These are staffed with employees from the country or the region. The local offices however are directly accountable to affiliates in the fundraising countries. It is unclear whether this model is conducive to local participation, or equity in decision-making.

Insights Worth Considering for the Wikimedia Movement

[edit]The following insights were pulled from the research, and deemed by the authors as relevant for beginning to answer some of the questions above. Some of these also are related interesting pieces of information that arose from the conversations with our interviewees.

Governance

[edit]Note: The research for this paper has illustrated again that the change areas of governance and revenues/resources cannot be considered separately. The previously published paper on the future of Wikimedia governance[5] pointed out the need to have the basic conversation about the governance model first (Global Advisory Council +WMF or General Assembly +Secretariat) to establish the context for further deliberation.

Seven out of eight of the the interviewed INGOs have the standard membership governance model with a general assembly and secretariat. This means that the respective movement features a higher degree of independent, diverse and contextualized affiliates. The practices of fundraising and resource allocation derive from this.

Regional Hubs

[edit]While regional offices and affiliates in the interviewed INGOs have different roles than what Wikimedia envisions for hubs, some of our interview partners pointed out the difficulties and pitfalls of managing national, regional and international levels of affiliates. These difficulties included communication lines, coordination of programs, and multiple layers of bureaucracy. Clear structures of subsidiarity in decision-making, especially around funding, are recommended.

Revenue Generation/Fundraising

[edit]In a model where everyone can fundraise, and where there is an expectation of self-sufficiency, economic inequities become apparent very quickly. Some affiliates will be able to raise more and do more, others will lag behind. This can become an inequity-increasing spiral.

Fundraising as a movement should be strategic, with those in strong markets building their fundraising capacity and relations, and those in weaker markets focusing on growing community and content.

Revenue Diversification is not an end-all, and not always a measure of success. Diversifying revenue at the level of small organizations can lead to drained capacity and mission creep. Focusing on what revenue source any given affiliate is strongest in, improving in that area, and assuring risk management promises a higher RoI.

Fundraising policies, for example on restricting income sources, or on home rule, tend to not be universally applicable, and are quickly contradicted by the need to make rational decisions. For example, an affiliate in Peru will have no income if extractive industries are excluded as sources.

In addition to home rule as a default, transparency, communication and collaboration on funding are crucial, as well as established affiliates sharing donors and revenues with emerging affiliates. Interviewees emphasized the importance of pragmatism and common sense to maximize revenue for the whole movement.

Resource Allocation/ Redistribution

[edit]The advantage of a policy-based redistribution system, in which funds are shifted between affiliates, is a higher degree of transparency and predictability in terms of the funds that go to regions and to affiliates with low fundraising capacity or potential. In addition, It would be a step towards improving equity in access to movement funds.

Three of the sampled INGOs have centralized redistribution systems, administered by the international entity. Each of these is very different from the other ones, both in terms of how contributions are structured and negotiated, and in terms of how disbursements are made. The redistribution systems have accountability and risk management components similar to a grant making scheme. They also assure accountability of those affiliates who contribute, and support a culture of solidarity, mutual support and global mission.

Redistribution systems are complex, and they require central infrastructure. The related policies and formulas are subject to adaptation and renegotiation every few years. This process requires participation of stakeholders and in the cases reviewed is done by working groups, various movement bodies and ultimately, the general assembly of the movement.

Each redistribution system has aspects that are useful for Wikimedia, should the movement consider moving to such a system. Additional information on them is available, in particular from the INGO with the most advanced system.

Participatory Decision Making

[edit]Note: Participatory decision-making is extensively covered by the paper “Designing futures of participation for the Wikimedia Movement”[6]. Participation in decision making about funding is in most of the cases built into the governance structures of both the overall confederation, as well as through the fact that affiliates independently fundraise and have their own accountability to their communities. Here too,it is obvious that governance and funding are not separable issues.

This concludes the research part of this paper. Following are a look back on the history of resource generation and allocation in the Wikimedia Movement, and a discussion of the components of Wikimedia Movement Strategy related to this topic.

Part II: Context

[edit]The Recent History of Wikimedia Revenues and Resources

[edit]Before 2011, Chapters were able to fundraise, or ‘payment process’ in their geographic context - 12 Chapters were doing this. WMF directed potential donors (i.e. visitors who click on fundraising banners) to payment-accepting chapters' fundraising websites by using IP address geographic lookup. To accept payments, chapters had signed a standard fundraising agreement. These chapters were expected to observe agreed upon standards around fundraising, donor privacy, and reporting; and to share revenues with WMF while supporting the global mission of Wikimedia.

But this, in the view of the then WMF Board of Trustees, created many challenges: Too much money went to a few chapters, who were not ‘ready’ to accountably deal with the sudden wealth. But one of the main problems was inequity, according to the Haifa Letter of the BoT:

This fundraising model has also contributed to significant resource disparity among chapters. Some of the largest fundraising chapters have revenue far greater than their stated need and capacity to spend, while other chapters receive revenue only from Foundation grants or have almost no revenue at all. The model also suggests that chapters are entitled to funds proportional to the wealth of their regions, which amplifies the gap between the Global North and South.

The ‘Haifa Letter’ announced the end of this situation - the board tasked the CEO to come up with recommendations for a new model, according to design principles outlined in the letter. The final board resolution put an end to payment-processing of most chapters, and laid the foundation for creating the grantmaking system henceforth known as the APG, with the Funds Dissemination Committee (FDC) as an oversight committee.

Revenue Generation

[edit]As a result of the changes, all chapters and affiliates, except for Wikimedia Deutschland and Wikimedia CH, today no longer engage in online fundraising in their countries. Banners were displayed on the project sites by the WMF and funds went to the WMF. Chapters of course were free to fundraise via other means, off the Wikimedia sites, and some of them did, while not having access to local donor data which remains within WMF.

Wikimedia Deutschland was the only chapter that ultimately took the decision to invest in online fundraising as an organizational capacity. The organization over the years grew membership to over 100,000 supporters. The fundraising agreement between WMF and WMDE outlines conditions and fund transfers. WMDE continues to transfer annual online donations to the WMF each year, and contributes significantly to overall movement funds in this manner.

The WMF built a professional advancement team, focusing both on the online campaign on behalf of the movement, as well as on major donor and institutional fundraising, and later on building an endowment. This was highly successful, with revenues from the online banner campaigns increasing more than fivefold in the decade 2011 -2021. WMF banner fundraising entered into a number of previously undeveloped markets and was able to make large gains.[7] Chapter fundraising accounted for in these figures comes from the two chapters who continue to do their own ‘payment processing’ in the established markets of Germany and Switzerland. It doubled in the ten years. The revenue from banner campaigns in the other strong fundraising markets across Europe and Asia is not disclosed separately at a country level on the WMF reports.

It is unclear how much revenue is lost to the movement due to the fact that online donors in those markets are unable to receive tax deductions for their donation, and that affiliates do not have systems or the data to establish lasting relationships with their donors.

Resource Allocation

[edit]In order to assure a level of community ‘say’ in decisions about fund allocation, the Funds Dissemination Committee (FDC) was created by a 2012 Resolution of the WMF Board. This group of elected volunteers was tasked with reviewing all proposals for annual planning grants (APGs), and working with chapters through any questions and recommendations they had. They then made recommendations about the APG proposals to the WMF Board. Funded recipients wrote extensive reports on each year for which funds were received, which were also reviewed by the FDC. The moratorium on new chapters increased inequity in funds allocation, since it created a situation in which, according to the FDC “that older organizations in Europe were able to receive greater amounts of funding through the program and others were not.”[8] The FDC was put on hold and was then dissolved when the Movement Strategy process was initiated. In a retrospective, the FDC shared recommendations on “decentralization of power and equitable distribution of resources”, which were informed by the years of learning about affiliates programs, capacities and accountability.[9] Over the years, there were additional grant types provided by the WMF, including low-hurdle project grants, event grants, rapid grants and simple APGs for smaller or emerging affiliates. In 2021, post-Movement Strategy, the grants programmes were restructured into three funds[10]. In 2021, regional committees[11] were established by WMF to add stakeholder participation in the short term and move towards funds allocation aligned with regional priorities and strategies in the mid-to long term. This model is still too new to draw conclusions about its potential for participatory resource allocation, but has already met with criticism[12], due to the complicated process.[13]

Intra-movement relations and culture

[edit]The decision to centralize the flow of funds had consequences beyond how much money was raised and where it went for what work. It shaped movement relations in ways that the BoT at the time probably did not foresee or intend. One of the first reactions was the attempt to create a Chapters association, in order to better advocate for chapters’ interests vis-à-vis the WMF.

After this failed, discussions about the fundraising model ended. APG grantees increased their budgets gradually, and along with it had to increase the time they spent on writing reports and proposals. At the same time, these grants afforded a luxury that most nonprofits outside of our movement do not have: a reliable, sustainable source of general operating funds, plus base program funds.

One of the often heard criticisms of this model took offense with the fact that the WMF, for its annual plan and budget, was not subject to the same review and accountability as other affiliates. For a few years, the WMF then submitted its annual plan and budget to the FDC. However, the WMF Board did not always follow the recommendations of the FDC when it came to the WMF budget. Here, the limitations of participation in resource allocation decisions became very apparent. FDC, in its retrospective[14] states:

The additional goal of review of the Wikimedia Foundation annual planning process was never truly realized. The principle of having the Foundation plans be reviewed by the movement remains important. A viable review process given the Foundation size and scope of operations still needs to be established as having it go through the same application process as chapters never adequately met the needs for review.

Over the years the funding process was revamped and restaffed several times. FDC members worked hard to keep up with all the proposals, however the workload was immense for a group of volunteers. Global metrics were discussed, implemented and discarded. Chapters and user groups remained critical of the processes, the amount of time it took, and the unpredictability of funds.

Fundraising beyond the online campaign was also a difficult issue for the movement, with collaboration among entities mostly non-existent. The WMF was able to successfully build relationships with major donors and foundations in the US, but often did not share these with other movement entities, or consult the appropriate stakeholders during development of externally funded projects.[15] Larger European chapters supplemented the APG income with institutional fundraising from private and public funds to a limited degree. Most smaller entities and individuals from the communities utilized the project and event grants for their activities. One the one hand this provided easy access to project funds for anyone, and gave Wikimedians ways to do things locally and informally. At the same time, creating sustainable Wikimedia affiliates was not a priority. This manifested in the 2-year moratorium on new chapters in 2013, as well as the subsequent exponential growth of user groups[16]. Since then, very few chapters have been added, and the budgets of existing ones that do not payment-process have experienced limited growth.

During the WMDE-organized ‘Chapters dialogue’ of 2014, much of the discontent around movement funding surfaced again. The process concluded:

Creating a consensus about money, its collection and responsible dissemination (donors’ trust!) is scarcely possible. The Haifa trauma persistently blights the relationship between WMF and the Chapters, fuelled by additional disagreement about the new fundraising and grantmaking processes.

Chapters Dialogue recommended “...the design of a framework for the Wikimedia movement in which it can work strongly and effectively towards its mission”. In 2017, the movement strategy process began. At this point, the level of trust between WMF, affiliates and communities, when it came to decisions about funding, was fragile. The movement strategy deliberations took a strong focus on reforming the resource management structures.

The Movement Strategic Direction, Recommendations and Principles as they relate to Renvenues and Resources

[edit]The Strategic Direction, published in 2017, was a broad, ambitious statement. It was the result of a nine-month input process engaging many stakeholders. It describes the roles of the movement in the world and in the ‘knowledge ecosystem’, as promoter of knowledge equity and provider of knowledge as a service. The endorsing organizations pledged to find the resources for implementation. But not until Phase II of the 2030 Strategy Process (2018-20) was the topic of money picked up again. In this phase, nine working groups of globally distributed movement staff and volunteers were formed to deal with the more operative and internal aspects of the movement and of implementing the strategic direction.

Draft Recommendations

[edit]Two separate groups dealt with funds: Revenue Generation and Resource Allocation. However, many of the other working groups touched on these issues as well. Each of the nine groups published their draft recommendations in September 2019 , before all recommendations were resorted, edited and merged in early 2020. The original funds recommendations included

Revenue Generation Working Group

(1) Turn the Wikimedia API into a revenue source

The APIs of Wikipedia and Wikidata are among the most widely used on the planet. While keeping the APIs free for everyone, we can offer “tiered” premium service for large users of our API such as Google, Microsoft, Amazon, and others. The tiered may cost between thousands of dollars to millions of dollars, depending on usage amount, and will enable the Movement to provide dedicated development time for the APIs, as well as services like dedicated API gateways or better provisioning of API regions, if those are requested by clients. Inspiration for this can be the GNIP / Twitter service, which has tiered support - the basic API is free for everyone, but access to the Twitter “firehose” (tweets generated in real-time) costs up to $100,000 / month.

(2) Provide Paid Wiki-related Services

The Movement can create professional and consultancy services around technologies (e.g. MediaWiki and Wikibase) aimed at organizations seeking to implement those internally.

(3) Monetize merchandise

Research merchandising and leveraging the Wikimedia brand as a new revenue opportunity. (license trademark, partner with other companies, etc. Research examples such as National Geographic and NASA).

(4) Expand global fundraising

Most of the Movement work with charitable foundations and individual major donors is focused in the United States. There is a large opportunity to develop fundraising worldwide in major gifts, foundations, legacy giving, corporate giving, and events. The Movement will need to develop the skills to fundraise effectively in different countries and cultures while always remaining consistent with the Wikimedia values and brand.

(5) Develop non-fundraising revenue streams for affiliates

Affiliates should develop in-kind donations and partnerships, EU and government grants, and earned income (consulting services e.g. with GLAMs)

(6) Set a goal of financial sustainability for all movement actors

All movement actors should strive to be financially self-sustaining and self-sufficient given the methods at their disposal, and to fuel the rest of the movement to the extent of their capacity

(7) Diversification of revenue channels

Expand payment methods available to readers worldwide and continually update methods with changing technologies to provide an optimized, localized, and convenient donation experience. (Examples: mobile payment methods, cash, local country methods.)

The working group primarily made recommendations around new and diversified revenue sources, but did not directly touch on the related structures and authorities. They do hint at a few ideas, however, in Recommendation 4-7, that put the focus on developing revenue generation outside of the US and EU, with an emphasis on self-sufficiency.

Resource Allocation Working Group:

- Set Common Framework of Principles for Resource Allocation

- Design participatory decision making for Resource Allocation

- Recognize privileges / Design for equity

- Distribute existing structures

- Build Thematic hubs – to provide services to the free knowledge movement long term

- Ensure flexible approach to resource allocation in a complex, fast moving and changeable space

- Allocate resources for capacity and sustainability

- Allocate resources to new types of partners/organisations (essential infrastructure of the free knowledge ecosystem)

- Include knowledge consumers

Recommendation D is central to the topic of reforming our movement funding structures as the MCDC is tasked with. Combined with the principles and values described in A-C, D makes a strong case for global redistribution and states:

A certain percentage of all movement resources will be allocated to global south countries. This percentage should be refined and researched in a later process but has a minimum value of 50%. This percentage of movement resources allocated to be spent in global south countries specifically includes all staff, senior management, and oversight bodies, in the global Wikimedia movement.

Recommendation B took aim at creating more community say in decision making about funds:

We recommend that existing decision-making processes be opened up to actors outside of the current decision makers. New decision-making participatory processes need to engage the strength, expertise and knowledge of communities impacted by resource allocation decisions. Communities which in the past have been only at the receiving end of resource allocation decisions, with no input in how those decisions are made, will continuously develop and adapt the decision-making processes in the future.

The working group had commissioned a piece of original research on the practices of INGOs around how decisions are made on movement-wide funds. It showed, among other findings, that the larger the amount of funding, the less involved are local or national affiliates, and the more power is executed by the ‘central’ entity.[17]

Recommendations E-H articulate preferences for what types of activities funds should be allocated - thematic hubs, capacity building, innovation, partners and new reader experience.

Final Recommendations

[edit]The final recommendations, after another round of community review and an extensive re-writing and editing process, were published in May of 2020. They do no longer include a recommendation focusing on resource generation and distribution. The 50% goal was removed. However, some of the original thoughts can be found across recommendations 1 and 4.

Recommendation 1

[edit]We will adopt more robust, long-term, and equitable approaches towards generating and distributing financial resources among different stakeholders in our Movement.

While curating, editing and contributing content are the most important activities of our Movement, we know that there are other significant contributions to move us towards knowledge equity and knowledge as a service. These include public policy and advocacy, capacity building, outreach, research, organizing, and fundraising. For the growth and sustainability of our Movement, these activities need to be better recognized and sometimes compensated in certain contexts.

...

We will empower and support local groups and emerging communities and organizations to tap into existing and new ways of acquiring funds and forging partnerships.

...

- Create a policy applying to all Movement entities to outline rules for revenue generation and to define what may be adapted to local context and needs. This policy will balance sustainability, our mission and values, and financial independence. In accordance with this policy, we will:

- Distribute the responsibility of revenue generation across Movement entities and develop local fundraising skills to increase sustainability.

- Increase revenue and diversify revenue streams across the Movement, while ensuring funds are raised and spent in a transparent and accountable manner.

- Explore new opportunities for both revenue generation and free knowledge dissemination through partnerships and earned income.

...

In our current setting, the vast majority of funds and staff are located in the Global North, causing an inequitable distribution of resources.

...

We are missing the potential that comes with a diversified global approach, technological advances, and various revenue possibilities related to the use of our platform and product. With almost all revenue streams passing through few Movement organizations, there are missed opportunities and continuation of inequity.

Recommendation 4 (Part 4, Participatory Resource Allocation)

[edit]What

It is essential that Wikimedia affiliates find paths for financial support to develop relevant skills, grow, build structures, and contribute to our Movement in an accountable and sustainable way. More participatory resource allocation processes will be created closer to stakeholders in order to ensure more equity and relevance to contexts.

Changes and Actions

- In the immediate future, the Wikimedia Foundation should increase overall financial and other resources directed to the Movement for the purpose of implementing Movement strategy.

- These additional resources should support new regional and thematic hubs and other Movement organizations in addition to existing Movement organizations and affiliates.

- In the near future, the Movement should play a guiding role in resource allocation. The processes for allocation should be designed through consultation and described in the Movement Charter. This transition to Movement-led guidance should occur in a timely fashion.

- The Global Council should oversee the implementation of the guidance given by the Movement as described in the Movement Charter, including recommendations for funds allocation to regional and thematic hubs and other Movement organizations while recognizing the involved organizations’ legal and fiduciary obligations.

- Based on frameworks set by the Global Council, regional and thematic hubs will facilitate resource allocation through approaches that are reliable, contextualized, flexible, and resilient to secure and sustain communities and organizations with multi-year plans.

- Funding systems will need to be flexible in terms of length, merging strategic goals of the Movement with local needs and directives, specifying mutual accountabilities, and opening pathways to local funding initiatives.

Rationale

Increasing access to money or grants will not alone be sufficient to address issues of inequity in how resource decisions are made or prioritized. Resources should be allocated in and by people in each context and tailored to address their needs. Resource allocation decision-making processes need to engage the strength, expertise, and knowledge of impacted communities. This way it will be possible to provide resources to support capacity building and empower our communities to be more sustainable.

Altering our resource allocation systems will ensure a more relevant and efficient resource distribution and will create more local agency and impact. A positive impact on the growth of the communities’ capacities and their sustainability will allow them to be more autonomous and accountable.

The Movement Strategy Principles

[edit]Many of the working groups had begun with writing principles building the foundation for the more or less concrete recommendations. These were merged into 10 principles now underlying the movement strategy. They give guidance in terms of the design of the new system for revenue generation and resource allocation. In particular, the principles of Equity & Empowerment, Inclusivity & Participatory Decision-Making, as well as Subsidiarity and Self-Management provide a clear value base for any resource-related reforms laid out in the charter. The Principle of Contextualization reminds us that not all rules and all strategies may apply in varying contexts of diverse communities and affiliates across the globe. Transparency and Accountability, as well as Efficiency are principles underlying any fundraising policies, as well as those regulating the use and stewardship of funds.

Appendices

[edit]Guiding Questions Emerging from History and 2030 Strategy

[edit]The Movement Strategy recommendations stop at outlining details on financial structures and systems. These will have to be agreed upon by movement stakeholders in the near future. Considering the history and the recommendations and principles of movement strategy, the WMDE research team developed the questions below to inform the research in this paper. This list, while neither exhaustive nor complete, can also serve to frame further discussions of the Charter Drafting Committee and all stakeholders around financial equity and sustainability.

Not all answers to these questions will have to be found in the Movement Charter. The fundraising policy is one place, as well as other policies that are easier to amend than a charter. This would assure agility in terms of adapting standards, formulas, agreements and rules.

Fundraising

[edit]What is the additional revenue potential of decentralizing fundraising and accessing donor markets through chapters directly?

Will the charter establish the ability of affiliates to conduct online fundraising in their countries?

In the future, how can local donor data collected by WMF be made accessible and available to chapters/affiliates?

If so, which standards and policies need to be developed that regulate the use of the trademarks in fundraising? How do policies best assure proper risk management?

How does the fundraising policy and practice assure transparency, accountability and collaboration in fundraising, avoiding competition?

Are there revenue sources or fundraising methods that will be globally off-limits?

To what degree should fundraising be decentralized, and what are functions that could be shared, for example through hubs?

Self-Sufficiency and Revenue Diversification

[edit]To what degree can all Wikimedia affiliates be financially self-sufficient?

What are some strategies for maximizing fundraising potential and diversifying revenue while not compromising affiliate capacity?

Resource Redistribution

[edit]How can a fair distribution of resources be reached?

Given unequal economic contexts and fundraising markets with vastly differing returns on investment, how does the movement create mechanisms by which funds are directed from where they are generated to where they are needed?

What are the political decision making processes and what is the policy and the mechanism (beyond the charter) regulating resource sharing? How often should it be updated and by whom?

Subsidiarity and Community Decision Making

[edit]How does the movement assure the inclusion of communities in fundraising and allocation decisions?

What potential do the recently started regional committees have in a future movement?

What are the rights and responsibilities of affiliates, in particular hubs, in terms of fundraising, intermediary functions and allocation decisions?

Which roles, competencies and functions in financial resource management remain with the WMF/ the Wikimedia Endowment organization, and which ones should be carried out by the Global Council/Global Assembly and/or a potential international Wikimedia secretariat?

Governance and Movement Structures of Screened INGOs

[edit]| Name | Highest Governance Body | Seat/ Corporate Forms | other decision making bodies | global reach | By-Laws/ Charter | Members/Chapters | notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transparency International | Annual Membership Meeting | Berlin | Board, Secretariat | > 100 countries | Charter | National chapters, individual members | Accreditation process |

| ICA | General Assembly | Global Office based in Brussels, four Regional Offices (Africa, Americas, Asia-Pacific, and Europe), | eight Global Sectoral Organisations (agriculture, banking, retail, fisheries, health, housing, insurance, and industry & services), and five Committees and Networks (gender, research, law, youth, and development). | 112 countries | Bylaws | 318 organisations (themselves associations) | membership package |

| WYWCA | World Council = supreme authority, convenes every 4 years, between World Council meetings, the World Board is the main decision making body | Incorporated body, possesses civil personality in accordance with the laws of Switzerland. HQ in Geneva | Regional and national associations of YWCAs | > 100 countries | Constitution | 105 members | The World Council includes representatives from the 100+ member associations affiliated to the YWCA movement and elects 20 women to the World Board, the governing body of the World YMCA, which includes representatives from all regions. |

| Oxfam International | International Board and a multi-stakeholder Assembly with | Registered as "Stichting" Oxfgam International in The Hague, Netherlands and as a foreign company limited by guarantee in the UK. Also registered in Kenya under a Host Country Agreement with the Gov. of Kenya (HQ in Kenya) | 'Affiliate Business Meetings' convened as required | 90 countries | Oxfam International Board Charter | 21 member organizations (= affiliates), independent organisations; other than that: country programs | Governance reform in 2017 - 2021 |

| MSF International | annual International General Assembly | Geneva, CH, International Association | Board of directors ( elected by IGA) | 70 countries | Charter, Chantilly Principles, la Mancha Agreement | 25 member sections independent that are national and regional orgs, with branch offices (plus 5 operational centers) institutional membership only if net fundraising contributor; section also possible if contribution from human resources | 'Within the different representative structures of MSF, the effecitve participation of volunteers is based on an equal voice for each member, guaranteeing the associative character of the organisation.' |

| CARE international | The Council (representative of worldwide membership) | CH, Confederation of members | Supervisory Board (Independent) National Directors Committee, Secretariat, Strategic leadership teams | common Code | 14 member organizations, + candidates and affiliates

21 Total |

||

| Greenpeace International | Council (annual Global Meeting) | Greenpeace International is a 'stichting' under the laws of the Netherlands. It is based in Amsterdam and its formal name is Stichting Greenpeace Council. | International Board (7 members) Global Leadership Team (7 EDs) International Director and Management Team | 55 countries | Articles of Association (by laws)

Rules of Procedure framework agreement between International and offices |

27 independent national and regional Greenpeace organisations (NROs) voting orgs and candidate orgs | not a membership association but global network |

| Amnesty International | Global Assembly | UK, Amnesty International Limited ("AIL") and Amnesty International Charity Limited ("AICL") | International Board (9 members), International Secretariat. Not a membership structure. | 149 countries | Statute | Sections in 70 countries. Also roles for groups, individuals and networks; Types of members: Sections, structures, national offices | recent Governance Reform |

- ↑ https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Resource_Allocation_Practices_and_Models_at_International_Civil_Society_Organisations.pdf

- ↑ https://meta.wikimedia.org/wiki/Wikimedia_Deutschland/The_Future_of_Wikimedia_Governance

- ↑ A good update on the localization debate can be found here: https://www.nuffield.ox.ac.uk/media/5189/ingos_leadership_report_final_single-pages.pdf

- ↑ https://interagencystandingcommittee.org/grand-bargain

- ↑ https://meta.wikimedia.org/wiki/Wikimedia_Deutschland/The_Future_of_Wikimedia_Governance

- ↑ https://meta.wikimedia.org/wiki/Wikimedia_Deutschland/Designing_futures_of_participation_in_the_Wikimedia_Movement

- ↑ https://meta.wikimedia.org/wiki/Fundraising/Reports

- ↑ https://meta.wikimedia.org/wiki/Grants:APG/Funds_Dissemination_Committee

- ↑ https://meta.wikimedia.org/wiki/Grants:APG/Funds_Dissemination_Committee#Advice_from_FDC_regarding_decentralization_of_power_and_equitable_distribution_of_resources

- ↑ https://meta.wikimedia.org/wiki/Grants:Start

- ↑ https://meta.wikimedia.org/wiki/Grants:Committees

- ↑ https://www.wikimedia.de/wikimove-site/podcast/episode-2/

- ↑ https://meta.wikimedia.org/wiki/Grants:Programs/Wikimedia_Community_Fund/Committee_review_process_and_framework

- ↑ https://meta.wikimedia.org/wiki/Grants:APG/Funds_Dissemination_Committee#FDC_Retrospective

- ↑ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Knowledge_Engine_(search_engine)#Controversy

- ↑ https://foundation.wikimedia.org/wiki/Minutes/2013-11#Movement_roles

- ↑ Resource Allocation Practices and Models at International Civil Society Organisations, International Civil Society Centre, 2019